Saint Helen's Island (French: Île Sainte-Hélène) is an island in the Saint Lawrence River, in the territory of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is situated immediately southeast of the Island of Montreal, in the extreme southwest of Quebec. It forms part of the Hochelaga Archipelago. The Le Moyne Channel separates it from Notre Dame Island. Saint Helen's Island and Notre Dame Island together make up Parc Jean-Drapeau (formerly Parc des Îles).

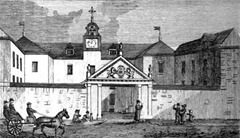

It was named in 1611 by Samuel de Champlain in honour of his wife, Hélène de Champlain, née Boullé. The island belonged to the Le Moyne family of Longueuil from 1665 until 1818, when it was purchased by the British government. A fort, powderhouse and blockhouse were built on the island as defences for the city, in consequence of the War of 1812.

The newly formed Canadian government acquired the island in 1870; it was converted into a public park in 1874. The public used it as a beach and swam in the river.

In the 1940s, during World War II, Saint Helen's Island, along with various other regions within Canada, such as the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean and Hull, Quebec, had Prisoner-of-war camps. St. Helen's prison was number forty seven and remained unnamed just like most of Canada's other war prisons. The prisoners of war (POWs) were sorted and classified into categories including their nationality and civilian or military status. In this camp, POWs were mostly of Italian and German nationality. Also, prisoners were forced into hard labour which included farming and lumbering the land. By 1944 the camp would be closed and shortly afterwards destroyed because of an internal report on the treatment of prisoners.

The archipelago of which Saint Helen's Island is a part was chosen as the site of Expo 67, a World's Fair on the theme of Man and His World, or in French, Terre des Hommes. In preparation for Expo 67, the island was greatly enlarged and consolidated with several nearby islands, using earth excavated during the construction of the Montreal metro. The nearby island, Notre Dame Island, was built from scratch.

After Expo, the site continued to be used as a fairground, now under the name Man and His World or Terre des Hommes. Most of the Expo installations were dismantled and the island was returned to parkland.

The island can be accessed by public transit, by car, by bicycle or by foot. The Concordia Bridge links St. Helen's Island to Montreal's Cité du Havre neighbourhood on the Island of Montreal as well as Notre Dame Island (which itself is connected to Saint-Lambert on the south shore by bicycle paths). The island is also accessible via the Jacques Cartier Bridge from both the Island of Montreal and Longueuil on the south shore.

©2017 Linda Sullivan – Simpson

The Past Whispers

All Rights Reserved